The Science of Aromatherapy: Ch. 1 Neurocircuitry of Smell

Neurocircuitry of Smell

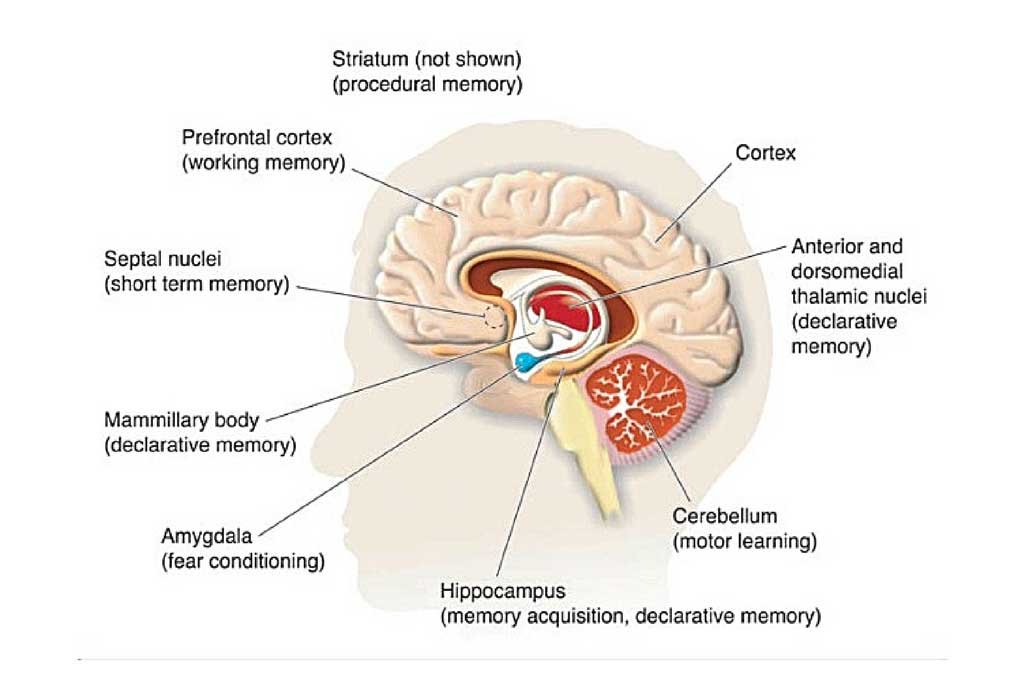

The sense of smell, or what is referred to in the scientific world as olfaction, is quite unique in its neurocircuitry. Odorant molecules start by binding to specialized olfactory receptors on olfactory receptor cells, of which there are millions. Interestingly, despite the various combinations of smells that our olfactory system can sense, humans only encode ~400 unique olfactory receptor types. You’re probably wondering, then, how this is possible. Well, smell is a combinatorial code of various olfactory receptor neurons being activated. So when you smell the brisk and energizing scent of peppermint essential oil, many different types of olfactory receptor neurons are firing to form a complex code that is sent through the olfactory nerve to the olfactory bulb. From the olfactory bulb information is routed to the piriform cortex, amygdala, hypothalamus, hippocampus and other limbic system structures through the olfactory tract. It’s due to the structural connections between the olfactory system and the brains limbic system that our perception of smell is intimately entangled with our experience of an emotion.

The Limbic System

As a neuroscientist with an expertise in psychiatric illnesses, I’d argue that the limbic system is one of the most beautiful circuits in the brain. It’s due to the psychological faculties regulated by these structures that it’s commonly referred to as the brains seat of emotion. Without getting too much into human neuroanatomy, let’s look at some of the major brain areas in this circuit.

The amygdala is our brains integrative center for emotions, emotional behavior, and motivation. Many behavioural neuroscientists that study the amygdala have focused on its role in fear and fear memory. Interestingly, studies suggest that odorants have the potential to trigger the recollection of strong emotional memories, the experience of which correlated with elevated activity in limbic brain structures, such as the amygdala. These odorants can lead to the recollection of both positive and negative experiences. It really depends on the memory that was encoded while the scent served as a contextual cue.

What is a Contextual Cue?

An example of contextual cues is as follows; have you ever had that experience where you have a thought to get something in another room but once you arrive in that new location you completely forgot what exactly that thing was? You then return back to the place where you had the initial thought and you now remember exactly what you needed? That’s a perfect example of context depending encoding and retrieval. Contextual encoding happens because of the spatial and memory consolidation properties of our hippocampus. In the case of emotional memories, the amygdala and hippocampus have a strong connection together. As such, the odorant serves as a contextual cue for the retrieval of the memory, the circuit is then activated and you re-experience an emotional state. Let’s do a bit of introspection, grab a notepad and write down 5 of your favourite aromas. Now write down a positive experience that you had that may have been paired with the smell and potentially explain why you like it. I’m sure that you’ve just discovered something that you never even knew about yourself.

Let’s look at one more important brain structure in this circuit, despite there being many more. The hypothalamus is involved in motivational behaviours and homeostasis (balance). It’s the part of our brain that regulates the hormones released from our pituitary gland. Motivational behaviours regulated by the hypothalamus include food intake, maternal behavioural, sexual behaviour, social behaviour, aggression and other simple behaviours. As for homeostasis, I think this is a great place to end our post and leave you in suspense as to the grand balancing act that the hypothalamus is well known for. I’ll give you a clue; it has a lot to do with our least favourite six letter word, STRESS.

By Daniel Michaels, HBSc, PhD(c)